|

| Colin Watson |

Colin

Watson was one of the funniest crime writers of his generation. His

Flaxborough series, featuring Inspector Purbight, sold well enough and

was televised by the BBC in the 70s under the title ‘Murder Most

English’ (starring Anton Rogers and Christopher Timothy).

He won two CWA Silver Daggers - for Hopjoy was Here and Lonelyheart 4122

- and he was elected to the prestigious Detection Club. After a spell

of being difficult to find, his books are again available and have

recently been republished in a new edition by Farrago. But Watson’s many

fans have nevertheless tended to feel that his work is less highly

regarded than it should be.

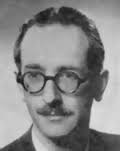

For those who know him, part of the fascination is the contrast between Watson himself and his creations. The few publicly accessible photographs of him show a somewhat diffident character with a neat moustache and horn-rimmed spectacles. HRF Keating describes him at Detection Club dinners as more or less disappearing into the wainscoting. Keating’s wife, meeting him at one of these dinners, thought that he was a schoolmaster who somebody had invited along. Appearances, as we shall see, can be deceptive, but his background was undeniably low-key and impeccably middle class.

Watson was born in 1920 in Croydon, Surrey, and educated at the Whitgift School, one of the smaller public schools, which he later claimed, ‘nearly always has the effect of putting one up against authority’. Watson left school at the age of 16 and in 1937 joined the Boston Guardian as a reporter, beginning a career in journalism that he was to continue on and off until the 60s. When the Second World War broke out, Watson was unfit for military service and spent six years working as a capstan lathe operator in a factory in Lincoln. After the war he returned to journalism, becoming a crime reporter and later leader writer, book reviewer and theatre critic for the Newcastle Journal. He also worked, in parallel with this, for the BBC in Newcastle.

His first novel, Coffin, Scarcely Used, was published in 1958. He continued to produce more books in the Flaxborough series, at the rate of one every couple of years or so, until 1982, the year before his death. He also wrote the (relatively little read) stand-alone novel, The Puritan and the iconic and quirky survey of crime fiction (mainly Golden Age), entitled Snobbery with Violence.

Let us therefore turn to the books. When HRF Keating’s wife did so herself, Rabelaisian was the only word she could use to describe them. Watson’s world is one in which doctors’ surgeries are used as a front for brothels, the main purpose of the local sand dunes is “desultory, gritty, fornication” and everyone has something to hide, even the most respectable citizens - actually, especially the most respectable citizens. To quote HRF Keating again, Watson’s books ‘view the baser parts of our nature … as hilarious farce’.

The Flaxborough series is set in Lincolnshire, where, as we have already noted, Watson had worked as a journalist and lathe operator, and to which he returned once he was able to give up journalism and write full-time. He describes Flaxborough thus:… a market town of some antiquity with a remarkable record of social and political intransigence. The Romans had lost a legion there; the Normans had written it off as an incorrigible and quite undesirable bandit stronghold, while the Vikings - welcomed as kindred spirits and encouraged to settle - had fathered a population whose sturdy bloody-mindedness had survived every attempt for eight centuries to subordinate and absorb it.

One thing that sums up Flaxborough for me is that, while most towns have a Coronation Street or Jubilee Terrace, Flaxborough has an Abdication Avenue. It is, as one of its inhabitants describes it: ‘a high-spirited town, like Gomorrah’.

Into this world, Watson places his characters. In Snobbery with Violence

he complains that characters in Golden Age crime novels have names like

Merrivale ‘exactly in the tradition of tennis-club literature, where no

one is ever called Ramsbottom or Golightly or Snagg’. No such problems

with Watson’s

characters. They include Stanley Biggadyke, Alderman Steven Winge,

Harold Carobleat, Walter Grope and, most gloriously of all, con-woman

and part-time detective Lucilla Edith Cavell Teatime.

Into this world, Watson places his characters. In Snobbery with Violence

he complains that characters in Golden Age crime novels have names like

Merrivale ‘exactly in the tradition of tennis-club literature, where no

one is ever called Ramsbottom or Golightly or Snagg’. No such problems

with Watson’s

characters. They include Stanley Biggadyke, Alderman Steven Winge,

Harold Carobleat, Walter Grope and, most gloriously of all, con-woman

and part-time detective Lucilla Edith Cavell Teatime.

Lucy Teatime assists the police in a purely unpaid capacity in many of the novels, sometimes to cover up things she herself has done. She arrives by train, in the fourth Flaxborough book, Lonely Heart 4122, when things get too hot for her in London. Her attempt to perpetrate a swindle via a lonely hearts bureau almost results in her death. She is, in a sense, the antithesis of Miss Marple. At one point she comments: ‘To tell the truth, it is regarding the physical side of marriage that I have always been apprehensive. There so seldom seems to be enough of it.’ In private she enjoys a cheroot.

But these are not amateur detective novels. The main character in most of the books is a policeman - Inspector Walter Purbright. Through the mayhem and corruption that is Flaxborough, Purbright moves, if not serenely, then patiently and invariably politely. He is a strange creation in the sense that he is happily married, does not drink to excess, and almost never loses his temper. At some point in the series, he gives up smoking. In Hopjoy was Here, he is introduced thus: ‘he stood loosely as if good humouredly apologetic for his bulk and looked around with his head slightly on one side, like a very high-class auctioneer deliberately ignoring the bids of merely moneyed men. He had the amused mouth of a good listener.’ And he is no fool. As one of his subordinates’ comments, there’s a streak of cleverness about him that doesn’t go with being a provincial copper.

Watson has the ability to produce very good portraits of his characters in very few words. One minor character he describes as looking like ‘a lady deacon at a farting contest’. Or there is PC Pook whose name is ‘like a formula in physics expressive of the nearest thing to non-existence’. Yes, Watson can move effortlessly from obscure physics notation to fart jokes in a single paragraph.

His one non-fiction work, Snobbery with Violence, was written in the early 70s and remains a classic of its type. It is both a review of crime fiction and an examination of why certain types of book became best-sellers and why others - his own perhaps - didn’t do quite so well. His contention is that anyone who wishes to sell a lot of books must genuinely share the views and prejudices of their audience. The first law of best sellers, he wrote, is that the author should have their finger on the common pulse and ‘a wide streak of mediocrity’.

He focuses on what we now describe as the Golden Age and illustrâtes its conventions through the invention of the village of Mayhem Parva - the sort of cosy environment in which amateur detectives of the 20s and 30s usually operated. It was clearly just down the road from St Mary Mead.

The setting for the crime stories by what we might call the Mayhem Parva school would be a cross between a village and a commuter’s dormitory in the south of England, self-contained and largely self-sufficient. It would have a well-attended church, an inn with reasonable accommodation for itinerant detective inspectors, a village institute, library and shops, including a chemist where weed killer and hair-dye might conveniently be bought. … There would dwell in Mayhem Parva a number of well to do people, some in professional practice of various kinds, some retired, some just plain rich and for ever messing about with their wills. The rest of the population would be working folk, static in habit and thought. Their talk, modelled on middle class notions of the vernacular of shop assistants and garage hands, would be a standardised compound of ungrammatical cheerful humility.

There is a lot in the book in this vein, and it is fair to say that few people (even Edmund Wilson) have devoted as much time to Golden Age crime fiction while professing to despise it. Watson condemns the writers of the 20s and 30s for their snobbishness and (returning to his other theme) their lack of talent. Of Edgar Wallace he writes: ‘trying to assess Wallace’s work in literary terms would be as pointless as applying sculptural evaluation to a heap of gravel'. Sax Rohmer’s ‘crude repetitive and often comic fury …failed to disguise an almost total ignorance of the people and countries he affected to find so sinister.’ Dorothy L Sayers was a ‘sycophantic blue-stocking’. He concedes however that Ian Fleming’s syntax was reasonably good - and in a rare burst of enthusiasm admits that Raymond Chandler never produced a dull line. Watson devotes a whole chapter to attacking Sidney Horler, whose work was ‘breathless trashy stuff’. Even Conan Doyle, from an earlier generation, was a third-rate writer who was 'as ready as any of his penny a line counterparts to lay hand on the hackneyed phrase and labour the obvious’.

Fortunately, you don’t have to agree with Watson to find the book entertaining. And his selection of writers to cover in detail - Horler and Rohmer for example - complements those in more recent surveys of the Golden Age. Snobbery with Violence is still well worth reading.

So, why did Watson fall from favour? I suppose I must concede that he was never a best-seller in the way that those he criticised undoubtedly were. Often the humour seems more important than the plots. And humour dates quite quickly.

The society that he mocked and satirised in his fiction no longer exists as a reference point. Some jokes have therefore lost their topical bite, others may offend some readers today in a way that they would not have done when they were written. As for his non-fiction, the Golden Age has been reevaluated and Watson’s attack, though entertaining and informative, now looks heavy-handed and unbalanced.

And yet, I would still respectfully suggest that he is worth another look. His style is exuberant and unlike any other writer. It is difficult to read one of his books without laughing out loud. Even when the plots are subordinated to the humour, they still work as plots. Julian Symons said that ‘in his hands the fireworks of comedy go up as they are meant to do in a dazzling show of stars instead of spluttering miserably into the darkness. All his books are genuine mysteries.’

So. they do and so they are.

The Flaxborough novels

Coffin, Scarcely Used (1958)

Bump in the Night (1960)

Hopjoy Was Here (1962)

Lonelyheart 4122 (1967)

Charity Ends at Home (1968)

The Flaxborough Crab (1969) - U.S: Just What the Doctor Ordered

Broomsticks over Flaxborough (1972) - U.S: Kissing Covens

The Naked Nuns (1975) - U.S: Six Nuns and a Shotgun

One Man's Meat (1977) - U.S: It Shouldn't Happen to a Dog

Blue Murder (1979)

Plaster Sinners (1980)

Whatever's Been Going on at Mumblesby? (1982)

Other works

The Puritan (1966)

Snobbery with Violence (1971)

L. C. Tyler was born in Southend, Essex, and educated at Southend High School for Boys, Jesus College Oxford and City University London. After university he joined the Civil Service and worked at the Department of the Environment in London and Hong Kong. He then moved to the British Council, where his postings included Malaysia, Thailand, Sudan and Denmark. Since returning to the UK he has lived in Sussex and London and was Chief Executive of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health for eleven years. He is now a full-time writer. His first novel, The Herring Seller's Apprentice, was published by Macmillan in 2007, followed by 8 further books in the series featuring Ethelred Tressider and his agent Elsie Thirkettle. The first book in a new historical series, A Cruel Necessity, was published by Constable and Robinson in November 2014. Since then, he has published six further books in this series. The latest being The Summer Birdcage

No comments:

Post a Comment